"Personal memories"

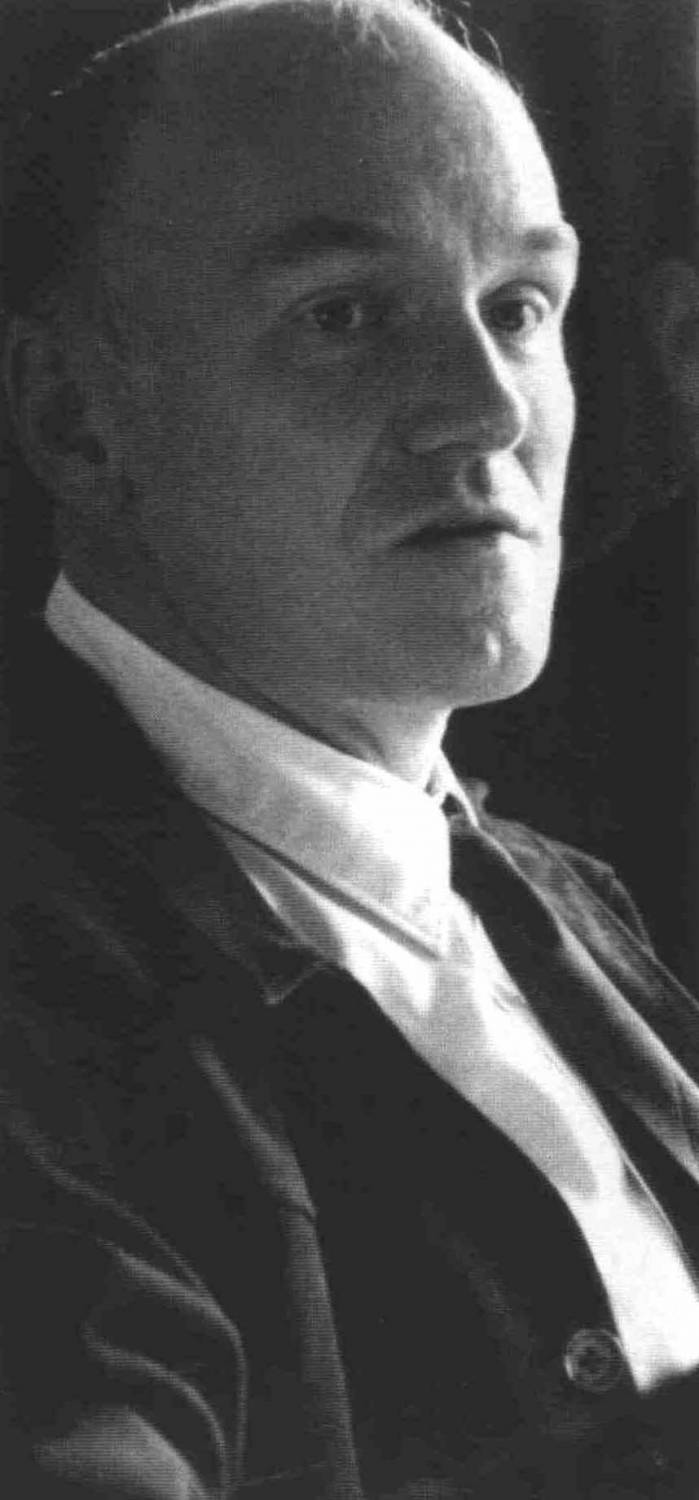

Prof. Lidia Baldecchi Arcuri

October 13th, 1962

It may be surprising, but my first reaction to the Maestro was one of bewilderment and his performance actually didn’t convince me.

He came onstage targeting that “black prey”, without a glance towards the audience, barely nodding. Not yet seated, he plunged on the Schumann Sonata. Astonished, I gazed and thought, “It will be either thumbs up or thumbs down. There was nothing lukewarm about this pianist!”

Of course, the verdict wasn’t thumbs down! We were evidently in the presence of genius, but his approach gave me an impression of nervousness on his part, which in turn triggered uneasiness in me.

Years later, I learned to foresee these moments of nervous tension (that had nothing to do with public performance because actually, audiences and the stage never really bothered him; but they were caused by the most unpredictable and - for me - incomprehensible reasons.)

I don’t remember anything else of the evening. I only remember that I was totally staggered by the tsunami that had struck me.

March 29th, 1965

…This time I was psychologically prepared to receive the onslaught, but it turned out to be useless!

The moment he uttered the first tone, all was revelation. He seemed to improvise each emotion and each emotional hue carried you farther and farther away from the actual instrument that was producing it. It was not piano playing! I don’t believe I had ever heard (or have since heard) such a visionary performance of the Chopin 4thScherzo. He had recreated the composer’s starting point.

That evening I completely succumbed to his sublime artistry, and my admiration grew constantly till the moment he left us.

November 25th-27th 1966

…Unfortunately I was out of town and did not attend these concerts, but I heard raving reports about them: it didn’t surprise me. By this time, nothing concerning Richter’s interpretations could surprise me.

June 14th 1969 (conducter: Riccardo Muti)

In 1969 Prof. L.B.A. meets Richter for the first time:

My encounter with Richter happened at Riccardo Muti’s wedding.

Shortly afterwards, he entered our home (and hearts) definitively. The occasion: Ravel’s Concerto for the left hand.

The conductor, Riccardo Muti had made his debut in Genoa one Saturday afternoon of years before and had, since then, become a dear friend of ours…

One of the most meaningful encounters of my life

My husband and I had been invited to Cristina and Riccardo Muti’s wedding in Ravenna.. We spent unforgettable days, not only for the event itself, but also for the uniqueness of its participants

My meeting with Richter had something surrealistic, but at the same time natural about it. This type of atmospheric situation, as well as others that highlighted some of his distinctive traits, often manifested themselves during our long friendship. I learned to recognize them, to understand them, to interpret, admire and to love them.These same traits remained intact –albeit sublimated – in his artistic universe: he possessed hyper-sensitive reserve as opposed to a total and often surprising spontaneity; his scathing instinct was integrated by an inflexible intellect; he could be child-likelynaïveor have sudden mysterious, unfathomable silences; he was indomitably curious; he was ruthlessly self-critical.

And now for the meeting itself. I’ll skip many delightful details that were later referred to me by Emy Erede, a lifelong friend of my husband’s - and Richter’s Italian agent.

The Maestro had entered surreptitiously into the last row of pews after the wedding function had already begun – obviously not to disturb or to be noticed! After the ceremony, if I remember correctly, we were about 100 guests waiting our turn to be shuttled to the lunch venue, when someone tapped me on the shoulder. It was Emy Erede who, with a twinkle in her eyes, whispered, “There’s someone who wants to meet you.” I generally take even strange events within my stride, and followed her with no particular expectation. To my complete utter astonishment, there in front of me - incarnate –appeared Sviatoslav Richter. I recuperated sufficiently to stammer some sort of lapidary salutation followed by a courageous entire phrase: “Maestro shall we be meeting again at lunch?” Equally lapidary, he answered. “No, at dinner.” And that was that! At dinner I found myself seated at his left, Emy Erede on his right.

Decisive events often “tiptoe” into one’s life. Our friendship was to continue, till the end, in this discreet reciprocal atmosphere of loyalty and esteem.

In the photo: the Church of Sant'Agata Maggiore in Ravenna

... dinner with Richter...

The dinner

The dinner took place on the top floor of an ancient palace of Ravenna. Actually, it was the meeting place of a group of melomanes and gourmets who came from every walk of life, each bringing the raw materials or the capacities and talents that better served their goal: good food and opera!temporary partition divided the cooking area from the dining area, which had been furnished with long rustic tables and benches. They called themselves

Gli Amici del Camino (

Friends of the Fireplace). In great display on the wall hung a gigantic photo of Pellegrino Artusi, legendary idol of the local Italian cuisine. A

temporary partition divided the cooking area from the dining area, which had been furnished with long rustic tables and benches.

Towards the end of the gourmet treat, a rhythmic drumming on the tables began that slowly developed into a “fff” crescendo and a stadium- type rooting of “Richter…Richter…Richter….!.

The Maestro, seated at my right, tried to escape the unexpected spotlight, (as he had done slipping into the church), but the rowdy insistence finally won over: he suddenly jumped to his feet, took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves and dashed towards a rickety old upright and sat down. After him dashed a group of the members, and to my astonishment my own husband, who appointed himself…conductor! How brazen could you be, I thought to myself embarrassed… instead everyone else was delighted (above all Richter and Muti!). Naturally they began with favourite operatic choruses chosen (by the chorus members!) at random: Richter (the orchestra) and the chorus were conducted by my husband.

At a certain point, a sort of operatic competition was sparked off, the competitors being: Nino Rota, Jacopo Napoli (then Director of the Milan Conservatory) and Sviatoslav Richter. They started challenging each others’ knowledge of Opera, pushing each other off the piano bench, hoping to play something that the others wouldn’t recognize. About an hour or more later, the “laurel wreath” was acknowledged - and Richter won. By the way, they didn’t certainly propose well-known arias…out would come I Lombardi Act 1, scene 2, or other such off-the- beaten- track repertoire. In his early years, Richter had accompanied opera for a living and had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the field. By memory.

At the end of the improvised competition, the greater part of the guests began to take leave. Richter came to me and with great simplicity said, “We’ll be seeing each other again in Genoa within two weeks time. I’ll be playing the Ravel left hand Concerto…even though I shouldn’t really do it!”(Emy had previously informed me that Richter’s wife, Nina Dorléac, had telegraphed him not to play it!)

I asked him if he would be our guest. “Naturally” he replied… and so it was to be ever since. What a rare privilege to have lived such unrepeatable experiences

A memorable appointment occurred on that 14th of June! Richter plays (for the first time) the Ravel Left Hand Piano Concerto, with Riccardo Muti conductor. A recording of the concert was published on the Stradivarius label, and our blog also refers Muti’s own testimonial. Such was the success, that the entire Concerto was encored at Richter’s own request, bypassing the orchestra’s understandable perplexity .

(ndr. The Italian recording includes the encore).

....I remember the rehearsal and evening this way:

He had promised to see us again soon, and so it was. Notoriously allergic to telephoning, ha had Emy Erede do it, inviting us to the rehearsal of the Ravel Concerto with Riccardo Muti conducting.

Upon arriving, one of his usual unpredictable surprises awaited Me.! He asked ME (!) to test the acoustics from different points of the hall. I timidly gave my opinion. He had the piano position altered and the rehearsal began.

He was visibly unsatisfied, but rehearsal time was up (the Union representative, member of the orchestra, was already pointing towards his watch…) Richter called Emy Erede and they confabulated. She came back, sat by me and said, “Unbelievable, he wants to pay the orchestra’s overtime, but he absolutely wants to repeat!” The orchestra thought twice about it, refused the offer, and the rehearsal proceeded. I was to witness many of these events which confirmed his complete detachment from the economic aspect of his profession and money “tout-court”. (“It’s not interesting”, he would always conclude.)

An after-dinner concert followed on our terrace (of course strictly with persons he already knew). That was the first of his many entries in our home for many years to follow.

It was early morning and the merry company was, at this point, enjoying the warm spring evening, when the Maestro suddenly took me by the hand and asked me to show him my house – which I did gaily! When we came to the kitchen terrace, amongst my herb vases he saw one that contained basil. I imagine he was not acquainted with it, because he asked me if he could taste it. I explained the Genoese specialty: pesto. He was as delighted as a child caught with his fingers in the jam. A moment later my husband appeared in the doorway, saw the scene, turned to me and without the slightest hesitation exclaimed, “Why don’t we start all over again? (at three in the morning!!) Make some pesto with trenette (a type of pasta) for everyone.” It was a “yes or yes” type of a situation, and so I did. The company livened up again at the fanciful idea and Richter ate the pesto-without pasta – by the spoonful. He was also like that!

Below some beautiful photos of Richter with his dear friend Lidia Baldecchi Arcuri on the terrace of her Genoese home (ca- 1992)![]()

![]()

![]()

August 9th, 1971

Piazza San Giovanni, Cervo, Imperia

We saw him arrive escorted by Sandor Vegh. He had a blue sea-captain’s cap tipped on his head. When he spotted us he opened his arms to their full extent and broke into a broad smile that suddenly turned terribly serious as he approached us. His first words were, “Tonight I’m going to play very badly.” My husband, extremely quick on the draw, answered, “Certainly, Maestro!” The answer – unexpected – offset him, so he gazed at us with his typically melancholic smile, waved, and off he went.

Before going on, I must divert to a rather interesting episode that preceded this extraordinary evening. Several days before, I had been invited to Milan for lunch at the home of the Baronessa Lanni della Quara where Richter often lodged when in town. As I entered, I heard the Schumann Symphonic Etudes in the distance. The Maestro was practicing what was to be the opening piece of the Cervo concert! Naturally my ears perked.

What I heard was one of the most peculiar and astonishing practicing I had ever imagined! Richter performed the composition, without pauses, from the beginning to the end, time after time again… We lunched without him to the faint background sound of Schumann. I had arrived late morning and left in mid-afternoon. He was still performing non-stop when I left. One of the times we later met (I don’t remember exactly when), when I asked him he explained the reason. He had always placed the “Etudes” in the last position of the first half, or somewhere in the second half of his programs. In Cervo for the first time, he had placed it as the opening piece. That was his way of understanding the “feeling” of its performance without prior contacts through other music!!!!

To get back to the evening in Cervo, the audience was already seated in the Piazza with no piano in sight. Finally the smaller pieces of the instrument slowly appeared, followed by the adventurous arrival of the principal body down the narrow steep ways of this medieval “borgo”, perched on a cliff--top that almost drops onto the sea. Vegh’s home was directly on the right-hand side of the Piazza and…on the edge of the cliff. Richter was hosted there and it was there that we went after the concert: but the concert still didn’t start. About another endless hour went by… the reason? The Maestro wanted the darkness to fall and the moon to rise!

Whatever his method of practicing, once he placed his hands on that keyboard, nothing else mattered. He seemed to have a “gold mint reserve” always ready to be lavishly spent. Artistically and emotionally he was a bottomless pit!

I find it impossible to even attempt to describe the three Chopin Nocturnes, but we all then fully realized the reason for his wanting… darkness to fall and the moon to rise.

After the concert we went to greet him. He was visibly satisfied (a rare event!). My husband couldn’t resist and let the occasion slip by: he embraced him, looked him in the eyes and said, “Maestro, that certainly is what I call bad playing!” The Maestro looked at us and melancholically smiled.

November 23rd, 1974 Teatro Margherita, Genoa

The seated ballerino

I believe it was on this occasion that Emy Erede informed us that she could no longer follow the Maestro, but that she was sure that we would have appreciated the person she had chosen to be her substitute. Milena Borromeo thus entered our lives and we certainly did learn to appreciate her! Emy also told us of Richter’s desire to be with us, and I was more than happy to organize the after-concert get-together.

As for the concert, I was not yet acquainted with the Miaskovsky Sonata, but I knew exactly what to expect from the performance of Shostakovich and Prokoviev. As usual, it was even more.

What I did not expect though, was that I would be hypnotized by Richter’s feet! I’m not speaking of his extraordinary pedalling (that perception was delegated to my ears), I’m speaking of the agile, complicated movements that he applied to balance his body in relation to the position and to the energy he wanted to transmit to the keyboard. In slow motion, I’m positive that a beautiful choreography could have been traced. He was a seated ballerino! I realized that during the entire evening, this illuminating discovery had made me completely ignore his hands. Could this be one of the secrets that “made the difference”? What I had seen that evening marked a turning point in my pedagogical and instrumental evolution!

He later confirmed my observation by explaining how the whole technical mechanism started from the floor.(This is an example of one of his many comments on technique; which obviously contradicts the grapevine gossip that “talking about technique” with Richter was taboo; actually, it was he who always started the discussion). The whole conversation started when, upon entering my home, he saw Beethoven’s Op. 106 on my music rack. He sat down on the bench and looking at the score, succinctly commented, “Unplayable!” Being acquainted with his performances of the Hammerklavier, I just looked at him and didn’t say a word. He continued.

“Finally a piano bench at the right height. Wherever I go, they want me to sit on the floor. Lidia, how can you do that if we must walk on our hands. To do that, everything starts from the floor and you must think upside-down. Are we or aren’t we acrobats?

The few words were branded in my mind, his tone lingered in my memory, and suddenly the actual vision of the workings of the balance of the entire body on the hands became my fundamental research. He was talking about body weight, not arm weight! What a revolution.

I’m referring this episode for the pianists who may eventually read these memories. As the Maestro would have said – pointing his index – “Investigate”!

Of this concert I still conserve his autograph on my copy of the Shostakovich Preludes and Fugues.

Even though during the following period he was absent from the Genoese concert scene, Richter came many times to Liguria when on his Italian tours. I went to Milan several times and was present in Mantova when the Decca label recorded a series of concerts in that acoustically miraculous theatre.

One of the Milanese concerts (1983) is also unforgettable for me. The concert included the César Franck Piano Trio ( with Oleg Kagan, violin, and his wife Natalia Gutman, cello) and of Debussy’s “Images” Book 2. Our encounter came about after an original opening “à la manière de…Richter”. Backstage an impenetrable crowd was waiting. Emy Erede picked us out and whispered us the name and address of a restaurant. It was the period in which he enjoyed dressing an ample black, red-lined cape. His fans didn’t knowyet, but Richter had already surreptitiously slipped away, helped by the darkness and …his black mantle! When we walked into the restaurant, he was already seated and greeted us merrily: he was apparently very pleased with his “operatic” exit from the backstage confusion.

He was particularly loquacious that evening; a relatively long period had elapsed since our last meeting. My husband instead was in lively conversation with Natalia and Oleg Kagan.

The following anecdote comes to my mind because it might be interesting for its technical implications: I told him of a concert I had recently attended during which – after the attack of the very first chords of the Brahms Second Piano Concerto– WHAM! the string broke. He put on an all-knowing expression: “Naturally”, he quipped (imitating precisely the gesture of the pianist concerned), “he uses his stiff forearm instead of his body. I’ve never in my life broken a string!!” He followed the statement with one of his typically naïve expressions which signified: “Really, it’s the truth, don’t you believe me?

Below: two postcards from Richter addressed to his friends Lidia and Domenico Arcuri.

Prof. Sarpero reports: For twelve long years Richter does not return to Genoa. During this period he tours Europe and gives more than 100 concerts, many of which in Italy. He furthermore goes to Japan and then makes a legendary tour of Siberia. On May 8th, 1986, he makes his return to Genoa with an all-Chopin recital, It remains one of my most intense memories of Richter performances of Chopin that even his best recordings cannot equal.

...The reviews report: “a triumph – without reserve!

May 5th, 1986

Teatro Margherita, Genoa

That evening we were all seated in the same row, one after the other: my husband, my pupils , and I.

Finally he had returned! What a return it turned out to be…

The first notes – the beginning of the Polonaise-Fantasie– were an absolute, unimaginable miracle. Not even he himself had ever managed such an achievement. The notes that follow the initial fundamental octave, (written in small type in the score and usually interpreted as a melodically melismatic passage), came out of the thin air as slowing-down and fading harmonics of the fundamental sound! We all simultaneously turned to each other, gaping. At the end, the applause didn’t merely break out, it exploded.

He faintly acknowledged the “explosion” and while it was still going on, dove into the first of twelve Etudes chosen: the Op. 10, n.1. I remember the left hand octaves as smiting bell-tolls and the savage right hand arpeggios. We were not only listening to piano playing: we were witnessing something visual as well. At the end the audience gave a standing ovation and I found myself Germanically stomping my feet. Suddenly Milena Borromeo appeared and signalled me that the Maestro wanted to speak to me. What could he possibly want this time? (A call during intermission usually meant that he was unsatisfied with his performance..) Impossible, I thought; instead that was exactly the case! He judged his performanceruthlessly, then added, “I can’t come to your house afterwards.” I just gazed and said, “That’s no problem. The only problem is that, according to what you just said, I must conclude that I’m deaf, I don’t understand the Etudes, and that I don’t understand Music in general! How can I be your friend?” He looked at me querulously and calmed down. Not I.

The four Ballades that followed were, and remain unequalled for all who were present with me in the hall. I returned backstage and stared at him. He smiled his melancholic smile and said, “Now I can come.”

He left at three A.M.

The particularly long 1986 Italian tour continued with the recorded Mantova concerts held in the Bibiena theatre (photo).

...digression...

Mantova concerts

Many memories come back to me of the Mantova concerts (besides the renewed joy of seeing the the beauty of this relatively small Italian “provincial” town.)

The local Communal administration had closed off the traffic near the theatre for the occasion (rare sensitivity, indeed, in our times).

This Teatro Bibiena had been inaugurated by the young Mozart, and Richter had discovered it (and its miraculous acoustics) during one of his previous explorations. His enthusiasm had induced Emy Erede to organize a series of concerts and the Decca recordings there. I personally don’t believe the recordings do justice to the “live” concerts. Apparently, during the recording sessions Richter also was not at all satisfied and it took all of Emy’s patience and tact to carry the project to its end!

Another anecdote comes to my mind because of its peculiar musical slant. It was a remark the Maestro made after playing an all-Schumann program which had included the “Paganini Études”. Again I was called during intermission, which immediately distressed me because of its usual implications. Instead he was smiling and with the expression which he usually assumed when saying something he knew to be original for me, said: “I love these Études because they are so Italian! And you know, Schumann is never Italian; he’s always so German”.

He also loved to pose musical questions to me “out of the blue”; especially abstruse and difficult ones! Once he suddenly asked me if I had the score of Hans Pfitzner’s Opera “Palestrina”. I gazed and said Noooo! He immediately pointed his index finger and said, “Why it’s the only Opera that talks about a musician: INVESTIGATE!” When I saw the score, the mere bulk of it scared me away and upon our next meeting I confessed my cowardice to him. He had a great laugh! (I think he did it on purpose). I have since heard the Opera several times: it’s lengthy but very, very beautiful and interesting.

Prof. Sarpero reports:

“…the 80’s through all the 90’s are turbulent years for Richter. Serious health problems afflict him, he suffers depressions, he is anguished for the loss of dear friends (Oleg Kagan, Emy Moresco…). Nonetheless, these negative events are balanced out by renewed impetus with the addition of new repertoire as well a refreshed return to some of his chosen repertoire. (He notoriously had one of the most extensive repertoires brought to the concert stage!)

During these years he frequently visited the Ligurean and French Rivieras, and it was from Genoa that he began his1989 tour in Italy; and it is on this occasion that he decides to begin the tour dedicating a concert to his long-time friend, Prof. Lidia Baldecchi Arcuri, to her pupils, and to the Conservatory “N. Paganini” in which she was teaching at the time. This is the chosen program:

Schubert: Sonata D.894 op.78

Weber n: Variazioni op.27 (Variationen für Klavier)

Szymanowski: 2 Metopes op.29 (L'Île des Sirènes and Calypso)

Bartok: 3 Burlesques op.8

Hindemith: ″1922″ Suite für Klavier, op.26

January 26th, 1989, State Consevatory of Genoa “ Nicolò Paganini”“Life's gifts”

I’ve always considered true friendship to be one of life’s most precious bestowals; and this event is a living proof of my belief.

As always when the Maestro decided to come my way, Milena Borromeo would call to give me the general details. I had, by then, an organized network of friends and pupils who suggested hotels, pensions or particular corners of the region that could meet his taste, and that…were new to him! This time the choice fell on a lovely hotel in Camogli that belonged to a friend of mine. It was there that we met him for afternoon tea. As always, we spoke of many events, of his health (he wasn’t in the best of shape), of facts in general and music, of course.

I remember one fact in particular because linked to another anecdote which took place shortly afterwards, and because it concerned the old diatribe about good and bad pianos.

A concert had been organized for him at the Soviet Embassy in Paris. The piano he was to play on turned out to be “the worst I had ever touched!”; but a refusal to perform, (which was his immediate reaction), was absolutely unthinkable. Then he turned to me tilting his head in his peculiar way, and with his typical expression (which meant, “really it’s the absolute truth!), he concluded: “It turned out to be one of the best concerts of my life.”

On the same theme, when I brought him to visit the hall and piano at the Conservatory, the Director came to meet him and had the unfortunate idea to excuse himself for the poor piano he had to offer him. I can still see him tilting his head, giving him a querulous and rather haughty look, and saying, “All pianos are good pianos for me!” That was that, and also the end of the story… I also believe that the concert that followed was also one of his best!

This is how it all happened.

Suddenly, out of the blue, the Maestro turned to me, and in his simple, dry style said, “I’ve decided to dedicate a concert to you, to your pupils, in your Conservatory” (

I couldn’t believe my ears);but, he continued, “I could play one of two different programs that I believe to be suitable for the occasion: one completely composed of

Études ( ! ) and another…the

other was the one I chose whispering the answer. I looked at my husband who had remained impassive at the announcement. I translated it as meaning exactly the same thing that had crossed my mind. Many times we may express

the wish and the will to do something which in effect we are unable to do for a number of uncontrollable circumstances. So I looked at him, thanked him (..

weakly!), conversed for some time still. The next day he left for Tuscany. I no longer dared nurture the idea that the incredible gift he had offered me would actually take place.

After a week, a call from Milena announced that Richter would give the concert the following week, on the 26th of January. I then realized that the Maestro never wasted his breath-

I immediately called the President of the Conservatory and the next day we met with the Director. When he told us that there were no funds to cover the minor costs of hosting such an event, I immediately set out to find them. The bank, Cassa di Risparmio offered the sojourn; Dott. Nicola Costa sent his private driver to pick him up in Tuscany and bring him to Nervi (a new destination to which he will return several times, and where, strangely enough, I now live). I personally took care of the tuner who worked for two days on the piano to make it worthy of the occasion and procured the small spotlight for the piano - (he had now adopted this discreet, almost mysterious type of lighting for his concerts). I then begged the local parish priest not to clang out the bells at Vesper time …and waited for the grand day to arrive.

The Maestro was thrilled with the accomodation and the sea-walk: everything suited him.

Turandot was on the billboard and he asked me if tickets were available. I procured them and off he went. The next morning he came but did not practice as I had expected: instead, there he sat at the piano playing and commenting the

tempos taken by the conductor in certain passages of the opera! As usual, my husband joined in and they

duetted until lunchtime. He wanted to lunch in the kitchen and so we did. I wasn’t aware that he didn’t particularly care for salads and I had prepared a rather complex one; fortunately he commented, “Oh, the first

interesting salad of my life!” For Richter, things were “

interesting” or “

not interesting”. Another example? The first time I saw him pull out of his pocket a conspicuous roll of money-bills, I told him to be careful. He looked at me and said, “Why, is money

interesting?”

He asked my opinion on what he should wear for the concert (he was very meticulous on the matter), and went to rest a bit. I arranged that he be accompanied by a pupil of mine, who also was to turn the pages, and went off to the Conservatory for last minute necessities.

A half-hour before the concert, the hall was already completely full and amazingly… silent! I was quite touched by the awareness of all these young people of the uniqueness of the event.

When the programmed time for the beginning of the concert arrived…no Richter! Fifteen minutes of complete anguish on my part, and total silence in the hall followed. Then suddenly my pupil appeared and, amused, told me that the Maestro had seen a deli and had stopped to eat some prosciuttoon a bread stick! I wewnt to greet his arrival, he looked around and ordered, “ Put on all the lights!”. The hall exploded in a prolonged applause with rhythmic calls of Richter, Richter…!

The rest is testified by the raving reviews and a recorded testimonial. It was and remains the most extraordinary gift received in my lifetime.

Post-script

After the concert, Richter did something so exceptional for him, that even the newspapers reported it: he sat down at the Director’s desk and autographed all the programs presented by the bubbling, now-noisy students!

During the quarterhour before he opened the door to the invading horde, he took me aside, visibly pleased and smiling said, “ In this program I intended to trace a journey from the Heavens (Schubert) to Earth; but to the licentious, dissolute, lewd Earth of Grosz (Hindemith Suite), Do you know him?” I answered negatively. By now you can guess what he said to me pointing his index: “Investigate.”

I did, and what a discovery it turned out to be!

Digression (by pure chance)

By pure chance, in 1995, I was asked to give some lectures for the coinciding commemorative year of Hindemith’s and Bartok’s birth. My investigation of the period had started shortly after Richter’s (imperative) suggestion to investigate.

The entire process initiated with the audition of a great part of Hindemith’s operatic, symphonic, solo and chamber works. My friend, Mrs. Orlandini, owner of a famous record shop of the time, helped me by lending me everything she had in stock. The link,

Hindemith-Grosz introduced me to the entire period of German Expressionism between the two wars and to the extraordinary Medieval Masters by whom they were inspired. This

Gothic heritage (not

Baroque as I had been taught erroneously!), was often declared by Hindemith himself. The

Baumberg Masters were the font of his inspiration and ideals. So I had decided to cover the walls of the Conservatory hall with huge posters of these

Medieval painters together with those of

Contemporary painters of Hindemith’s period. A truly astounding similarity resulted. One of the posters, representing a wooden Madonna of a

Baumberg Master was to be the visual background to a performance of Hindemith’s

“Marienleben”, Opus 27 for voice and piano.

As I was kneeled on the floor at home, reinforcing the Madonna poster for its placement on a stand, the phone rang. It was Milena keeping me posted.

“By the way,” she concluded, “the Maestro tells me to tell you how difficult the piano part to the Marienleben lieder is!” (He was to perform them during his Festival at the Grange de Melais, and I knew nothing about it.). By Pure Chance.

A FLEETING REMEMBRANCE

A church steeple

![]() O

On one of our jaunts dowm the coast, I noticed the Maestro searching for something in the landscape (?) His visual memory was phenominal. Suddenly he exclaimed – happy as a lark – “That’s what I was looking for . There it is!” It was the baroque steeple of the church of a small ex-fishing village; Sori.

He asked me to look for a pied-a-terre for him there. The task was more difficult than it might sound , because he wanted it “right under or in front of the church”.

I had found something, but he later chnaged his mind. Not unusual!

SOUND AND SPACE

(digression and after-thought)

I have just recently connected certain readings with certain choices taken by Richter during the last part of his extraordinary artistic career. In the program notes that appeared in the halls, he explained the reason for his determination to play in near darkness. What he never explained though, was the why of his concomitant choice to play only in small environments. From this consideration, I am naturally excluding the argument that small spaces are the dominating feature of numerous aesthetically enticing structures of the past: (for example, the small theaters of Mantova, Sabbioneta, Vicenza, Imperia, etc.). During my literary wanderings I fell upon an interesting conclusion of Peter Brookes, theatrical director, that could coincide with similar intimate needs felt by Richter in his later years.

The book is entitled “The Shifting Point” (“Il Punto in Movimento”). The chapter is subtitled

“Filling in empty space.

The use of space as an instrument”.

I have come to the conclusion that “theatre” is based on a specific human “necessity: that is, a yearning necessity to establish a new type of intimate “rapport” with fellow creatures.(…) In large spaces one is obliged to speak with “greater emphasis, in a less spontaneous style; if instead we could shorten the “distances; if all of us could get closer to one another, the intercourse, the “exchange, would become much more dynamic

Richter was a great “connoisseur” of theater and theatrical methods. He knew the techniques and the needs of projection “towards” and “through” space. Could it be that he also, at a certain point, had felt an urgent need to establish a new, a more intimate, a more dynamic rapport with his fellow creatures?

Unfortunately, at the time I didn’t ask him. Now I certainly would.

FLOWERS

He preferred white flowers, but didn’t follow his predilection when he offered them. What he did follow though, was his innate generosity. Regularly, flowers from Richter transformed a living room into a greenhouse and Mrs. Orlandini, owner of the record shop (whom I have already mentioned), became the object of one of these gifts. I don’t remember on which visit to Genoa he expressed the desire to visit a record shop, but I do know that he had written a letter to the specialized magazine MUSICA denouncing the reproductions of some CDs that (according to his judgment), were not up to his standards, and therefore not personally authorized. I believe the letter was written after our visit to the shop.

I brought him to the above mentioned shop and asked for the owner. When she saw whom I had brought, she broke out into tears! I remained rather stunned and Richter was visibly touched by this unexpected emotional encounter. He looked her in the eyes hinting his typical melancholic smile. He then asked her to vision all his recordings. She opened numerous drawers packed full. He chose a certain number, and then asked me to follow him out of the store. He had obviously noticed a violet vendor on the street corner while passing by, and pulling out the usual roll of bills from his pocket, handed them to me saying, “Buy the basketful.” Notoriously those baskets are composed of several dozen very small bunches that are rather costly. I felt the necessity to remind him of the detail. “The basketful”, he insisted, “the lady has many sorrows.” Superfluous to describe her reaction. The Maestro had reacted in his way: with extremely refinedpsychological insight, and great humanity."

a) The visit probably took place during the days near the concert held in Chiavari in March 1990.

b) The letter to MUSICA refers to the Maestro’s communication to the magazine and is printed in

n. 60 of Feb./Mar. 1990. It reads:

“I must point out to your readers how a certain number of my recordings has been released by “editors who lack any type of cultural or artistic criterion. The result is the coexistence of “performances of value, or at least of validity, and others that I don’t hesitate to qualify as “rubbish. The non-authorized release of discs of such poor standard cannot but generate in the “listeners doubts and even bewilderment. What can have moved such initiatives? Is their goal to “serve Art and to inspire listeners? Or could it be simply a commercial transaction?”

HOW HE PRACTICED

(and other enlightening musical thoughts)

I’ve already mentioned how I heard the Maestro practice the Symphonic Études before the Cervo concert in the home of the Baronessa Lanni della Quara. Throughout the years though, I concluded that he always changed his practicing method according to the immediate problem he was about to face. In the case of the Schumann Études he was placing them for the first time as the opening piece of the recital and therefore felt the necessity to feel them without having warmed up. What I can testify as being the most recurring method, was that he almost always practicedpiano or pianissimo. He was barely audible even in the adjoining room (and my home was certainly not well isolated!). When I mentioned it to him, he nonchalantly answered, “When you know how to play pianissimo, fortissimo is no problem!”

Another recurring method was that he rarely practiced the compositions he would be performing on the same day or on the day after. The days before his concert in the Conservatory, he practiced only Debussy and Liszt Transcendental Studies. It was stupefying to hear the finished product, (in tempos, phrasing, differentiations of hues…), but all kept within an intensity range from a ppp to a maximum of piano– an absolutely unbelievable feat! (I thought that if all pianists adopted such a system, what a beneficial effect it would produce on the neighborhood!)

He recommended another way to practice, probably reinforced by the incident he had mentioned to me, (and also narrated by Maestro Berlinskij of the Borodin Quartet), of the lights going out during a concert. He often practiced in the dark. “It develops and strengthens your inner vision of keyboard spaces in relation to the dimensions of your gestures, and to the exactness of your judgment of your own body in space”. I personally adopted it and it worked wonders. I suggest it to my pupils, but wouldn’t swear on their adoption of this extraordinary method of practice.

Another very interesting incident (for pianists and musicians in general) concerns Urtext editions. He was to play some Chopin Impromptus in the Chiavari recital and had forgotten the score. He asked for mine. It was the Henle Urtext edition that contains rather conspicuous differences from most of the other preceding 19th and early 20th century editions. He played certain passages for me over and over again, always asking, “Which do you reallyprefer?”. I was intimidated that he was asking my opinion, but I answered, and we finished by agreeing that our preferences did not fall on the Urtext edition! He remarked, “You see, now it’s the fashion to take these first editions as gospel truth. They aren’t! The bottom line remains that, what really counts is your personal acquaintance with the entire production of a composer, your imagination and your good taste.” After the concert held in La Spezia, I saw he was using a battered and torn edition of the Well Tempered Clavichord. Edition??...Mugellini! He saw me looking at it, and with his usual innocent expression (that signified, “really, it’s true, believe me”) said, “ Do you know, it really has some extraordinary intuitions. Why don’t they use it more often?”

Again, he had demolished, forever,another of my restrictive, academic prejudices!

ON FIDELITY to the score and TRUTH

When asked what the secret of his interpretations was, he often answered, “Maybe because I can read a score better.” He was totally convinced that his interpretations were the result of mere fidelity to the written score: that the truth of the composer emerged when, as an interpreter transparency became the rule.

Especially in his case, I don’t agree. I can easily agree that subjectively, yes it is the rule: objectively, I believe it to be highly improbable, if not impossible to realize. I shall try to document my thought by quoting an interesting book: “To Say Man” by Marko Ivan Rupnic. (Ed-Lipa)

“…in our time it is neither interesting nor acceptable to speak of an absolute and only Truth, in so far as we are all subconsciously convinced that each and everyone of us possesses his own and that it is individual, intimate and unique. In fact one of the heritages of our époque is this newly acquired awareness of Truth as plurality. It is also true though, that roots of fundamentalism (the conviction that only one truth exists and that all should abide by it) are as widespread, if not even more. Again, others conceive Religion and Truth to be indissoluble, therefore they believe that those lacking religious creeds cannot possibly accede to The Real Truth. Actually, these are all comprehensible reactions to the historical moments we have lived and witnessed…”

Rupnic continues by examining the numerous trends of thought of the predominant civilizations of the past. I am particularly intrigued and attracted by that of ancient Greece and feel it is obviously applicable to Artists in general; but in particular to the phenomenonRichter.

“For the ancient Greeks, Truth includedall that was worthy of being collectively remembered. It was that which was constantly present; it was something never really buried or forgotten; it was that which was not subject to fashion or customs and thereby capable of overriding the temporal element. It is this absence of the time element which permits one to rediscover it and to contemplate it repeatedly.

Truth is therefore an “engraved eternal memory”, or a “perennial memorial”.

On the other hand, Greek thought also established that “The Eternal” could exist only within the Olympus of the gods; that humans, destined to inhabit the “Kingdom of Shades”, were limited merely to the elaboration of opinions.

Subsequently the gods fathered the Muses who were meant to preside specifically over all artistic creation. It followed that the “earthlyTruth” of humans, under Their protection and guidance, could to a degree,(by means of inspirations, creations, and the ideas of philosophers, artists and poets), draw from the “divineTruth”. Humans, destined to a world of opinions, were thus allowed access to sudden illuminated glimpses of the Olympic “reign of Truth”, which, in even the best of cases, was composed of only fragments of the “whole”.

The interpreter, in order to bring to life a work that without him would remain unheard and subsequently unknown, is in turn and in my opinion, if not a creator a re-creator. It follows that in the case of Richter, I really don’t believe that he was in the position to judge or to separate that which composed his individual, unique engraved (genetic) memory from a universally recognized memory as Truth.

He was simply endowed by the Muses to be illuminated by, and to participate in sudden glimpses of the divine Truth. He wasn’t in the least conscious of it and attributed it to fidelity and good score-reading!!!

HIS BACH

"My teacher,” he once confessed to me, “years ago told me that I didn’t know how to play Bach! So I just sat down and didn’t play anything else but Bach for almost one year.” We heard the result in a series of concerts that featured the performance of the 48 Preludes and Fugues of the Well Tempered Clavier one evening after the other. What a result it was!

Years later he made another comeback after another absence from the concert platform in Florence, not only with a Bach recital, but hand-in-handwith Bach! The impression was that of eavesdropping on a friendly chat between two old friends. During intermission I rushed backstage, literally walking on clouds. The Maestro was there next to Nina. Without even greeting them, I remember just embracing him and saying, “ Finally I understand! I think I know what you mean. His music is similar to visioning the simultaneous existence of many small solar systems: if you are within, you perceive stillness; if you observe from without, everything is in motion.” They both smiled and suddenly Nina took a step backwards and with a large gesture of the arm, pointed towards me and said to the Maestro, “May I introduce Lidia?” I obviously had understood… and was surprised and extremely flattered by Nina’s words. It was followed by a hearty laugh. I returned to the auditorium and continued to assist to the pronouncement of an eternal Truth

******************

I had suggested Santa Margherita for his next sojourn in Liguria. Unexpectedly a billboard with a recital program (all Bach) appeared in front of the Hotel Miramare; lodging that I had indicated. Intermission arrived together with Milena’s now usual request to go backstage. Again he poured onto me his total discontent with himself. This time the reason turned out to be (what he sustained had become) his overpowering incapacity to concentrate. Since I had not had the slightest inkling that such a incident had occurred, (it had been an incredibly transparent and precise performance!), I contradicted him. I don’t know whether he took my opinion into consideration or not, I know only that he went on to explain to me the basic difference between the French Suites (which he had just played)and the English and German Suites (Partitas). In the middle of this incredible disquisition (I was totally hypnotized by the novelty of his analysis!), my husband broke in, totally shattering the atmosphere. There was always a sort of theatrical and happy rapport between them, and this event lived up to the premises. My husband took his hands, kissed them and kneeled down in front of him. The Maestro threw back his head laughing, and quick as lightning pulled him up, and in turn kneeled before him! This interruption was beneficial because it made me somehow put aside my anxiety and Richter returned to the stage forgetful of his previous discontent and donated us an unforgettable French Ouverture.

With the “Eco” section, he once again gave us a “glimpse of the Truth as defined in the Olympus of the gods”.

CHIAVARI, the TURNING POINT

From the first phrases of the Mozart Sonata Iperceived that something had radically and definitely changed within my dear friend: only music is capable of transmitting such subtleties and hues of the soul. I kept hoping that it wasn’t true; maybe it was I who was misinterpreting. I intensely tried to transmit my plead to him: “ Please, don’t give up. We are in such dire need of your visions, of your message!”

Two Chopin Impromptus followed, but the atmosphere of a final withdrawal persisted. At intermission time, Milena approached me with a preoccupied expression and announced that the Maestro wanted to see me urgently. She informed me of Oleg Kagan’s last meeting with him in Imperia and that not much time was left for his friend. This communication strangely tranquillized me: there was now a tangible reason for his grimness, which could exclude a lasting and definite surrender.

As soon as he saw me, he began to pour out the conviction that he also, would soon be struck by the same pathology as his friend. He always travelled with his previous medical history, so I made an appointment for the Monday morning with the most qualified professionals in the field (the next day he was to play in Savona), hoping in a clearing up of the situation. It was not to be.

All that I had hoped happened the next day in the lovely theater of Savona. From the first notes that resounded (always a Mozart Sonata), we were all again mesmerized by the mere quality of his tone: let alone the music itself! How relieved I was. My relief was to be short-lived, because when I went backstage Nina had hurriedly arrived to take him back to Germany, where Richter’s personal doctor and friend lived. He had not been mistaken. For thy umpteenth time he underwent an operation. Fortunately it proved to be benign and we were to enjoy his revelations still for several years.

I must confess a certain difficulty in putting order into some overlapping memories. The incident I would like to narrate took place in my dining room, where we seated one in front of the other. We were drinking a cup of Chinese tea when he suddenly looked at me as if I could somehow qualm his inner turbulence. “Why am I still alive?... I shouldn’t be…. I don’t want to be! … I’ve had a long, full life. I’ve done my best and feel that I have nothing more to say.”

He was now putting it into words those sensations I had captured. This was now a reality, they were no longer mere subjective sensations. What could I say? I could only temporarily lend a helping hand out to my long-time friend: to a friend who had also personified an artistic ideal nurtured during my entire lifetime. “You will always reveal Truths unknown to the most”.Then, too touched to continue, I immediately tried to scale down and to minimize:“It’s such a splendid mild sunny day, you’ve had a marvelous walk – something that you’ve always enjoyed, and here we are still together able to exchange thoughts over a delightful cup of tea.” He didn’t answer, but smiled his usual melancholic smile, and we passed on to other topics.

Yes, he did return amongst us, but in a totally different dimension. As always, it was with total moral integrity and spiritual courage. He was going his Wayinto regions of rarifiedatmospheres where the air was to thin for normal lungs. Of course, again he chose Bach.

THE LAST CONCERT IN LIGURIA

It was to be his last concert, but not his last stay in Liguria. It was held in La Spezia and included Bach in the first half and Brahms in the second. The program represented his personal extremes: luminous intellectual assertiveness and dark, mysterious introspection.

The Bach was stereophonic. He was obviously producing this layered polyphony onstage but our perception of its provenance was multiple. He was occupying every corner of space in the hall! Furthermore, no strata was above a forte. Absolutely miraculous.

In Brahms, the logic that governed the sweeping emotions and the total freedom of their structure was overwhelming. When I went backstage he was visibly serene and satisfied, but…. still a doubt emerged in him. He looked at me querulously and said, “Tell me the truth, was I too sentimental in Brahms?”

I was to meet him again, but it was the last time I heard him in concert.

Prof. Lidia Baldecchi Arcuri

from "I Concerti in Liguria"

.jpg)