"N e w R e l e a s e s" (Novità Audio/Video)

L e R e c e n s i o n i

Registrazioni audio e video di recente pubblicazione recensite dal blog

A cura di Giorgio Ceccarelli Paxton

Luglio 2014

XXIV

LEGENDARY RUSSIAN PERFORMANCES

Concert in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory - 4 aprile 1949

Poche ma notevolissime uscite nel secondo trimestre di quest’anno.

L’etichetta russa Aquarius (http://www.aquarius-classic.ru) ci aveva già proposto qualche tempo fa su AQUARIUS AQVR 358-2 il bel concerto di Richter del 30 maggio 1949 a Mosca (vedi recensione su questo blog). Ora esce un interessante documento storico (AQVR 386-2) in cui, oltre ad altri importanti artisti sovietici, è presente anche Sviatoslav Richter in tre esecuzioni di brani di Rachmaninov.

Il concerto fu eseguito il 4 aprile 1949 in memoria del famoso e grandissimo pedagogo KONSTANTIN IGUMNOV, uno dei fondatori, insieme a Goldenweiser e Neuhaus, della scuola russa del pianoforte.

Konstantin Nikolaevič Igumnov (1873-1948) studiò a Mosca con Pavel Pabst, maestro oltre che di Aleksandr Goedike e di Nikolaj Medtner anche di Goldenweiser. Vinse il premio Rubinstein nel 1895 insegnando nei due anni successivi a Mosca, poi a Tiflis e ancora a Mosca in cui fu direttore del Conservatorio dal 1924 al 1929. Egli fu importante oltre che come insegnante anche come concertista soprattutto per la sua straordinaria paletta timbrica, melodiosa e piena di ritmo.

Le sue esecuzioni erano molto intimistiche e il suo modo di insegnare richiamava questo aspetto unitamente ad una grande signorilità. Era un vero intellettuale, nonostante la nascita in una piccola città di provincia, Lebedjan, nel sud della Russia. Usava dire di se stesso: “Posso dire che non ero interessato solo alla musica. Ciò che mi commuoveva era la natura, l’arte e i sentimenti morali e religiosi”.

Igumnov insegnò al Conservatorio per quasi mezzo secolo, avendo in totale più di 500 studenti che, nonostante le ovvie diversità, avevano in comune una cosa: un atteggiamento romantico verso la musica, affinchè – per usare le parole di Igumnov – “la musica risuoni come un linguaggio umano in cui siano scritti poemi, storie e versi. Il compito degli esecutori è quello di recitare questi poemi e questi versi”.

Tra i suoi allievi più famosi figurano Lev Oborin, Jakov Flier, Rosa Tamarkina e Marja Grinberg.

Konstantin Nikolaevič Igumnov

La caratteristica del cd che stiamo presentando è che gli esecutori non furono discepoli di Igumnov, come in altri concerti tenuti in sua memoria, ma artisti provenienti da altra preparazione pedagogica, segno questo della enorme stima che circondava Igumnov, a prescindere dall’estrazione storica dei singoli artisti.

Il concerto si declinò in due parti con diversi artisti coinvolti

Prima parte

1. Bach - Prelude

2. Bach - Fugue in g minor BWV 578

3. Rachmaninov - Trio élégiaque No.2 in d minor "In memory of a great artist" op.9

4. Liszt - Aux cyprès de la Villa d'Este

5. Rachmaninov - Prelude in g sharp minor Op. 32, № 12

6. Rachmaninov - Melody in E major Op. 3, № 3

Seconda parte

7. Rachmaninov - In the silence of the secret night

8. Rachmaninov - Oh no, I beg you, do not leave

9. Rachmaninov - How much it hurts

10. Čaikovskij - Not a word, my friend

11. Čaikovskij - Mild stars shone down on us star

12. Čaikovskij - The fearful minute

13. Čaikovskij - None but the lonely heart

14. Čaikovskij - Serenade ("Oh, child...")

Questi furono gli interpreti:

Alexander Goedicke, organ (1, 2)

Lev Oborin (piano), David Oistrakh (violin), Svyatoslav Knushevitsky (cello) (3)

Sviatoslav Richter, piano (4-6)

Pavel Lisitsian, baritone (7-9), Nadezhda Obukhova, mezzo-soprano (10-14)

Matvey Sakharov, piano (7-14)

Presenter - Valentina Solovyeva

Al netto dell’interesse storico che tutte queste esecuzioni propongono, vi è il “nostro” Sviatoslav Richter con i “suoi” inimitabili Liszt e Rachmaninov, che, benché limitato ad una quindicina di minuti complessivi, mostra e conferma quale formidabile artista già era in quegli anni e sarebbe poi definitivamente diventato. Da notare che i tre brani qui presentati sono nuovi alla discografia richteriana, in quanto finora circolanti solo su registrazioni private di collezionisti (del brano di Liszt è disponibile solo una registrazione del 1956). Ulteriore elemento questo, oltre alla caratura artistica degli altri interpreti, per solleticare l’interesse per questa produzione.

S. RICHTER - BEETHOVEN – MOZART – VISTA VERA VVCD 00255

Ancora una ottima produzione di questa etichetta di origine russa che ci presenta il quinto cd praticamente dedicato a Sviatoslav Richter (per i precedenti vedere le recensioni su questo blog). La menzione “volume 3” fa ben sperare in altre pubblicazioni richteriane in futuro.

Molto interessante questo disco che contiene due Sonate di Beethoven e un Concerto di Mozart.

Cominciamo dal Concerto nr.20 in re minore KV 466 di Mozart nella esecuzione moscovita del 18 maggio 1958 con Karl Eliasberg alla guida dell’Orchestra Sinfonica della Filarmonica di Mosca. Questa esecuzione del KV 466 (concerto che Richter eseguì moltissime volte con diversi direttori tra cui quelle con Sanderling, Kondrashin, Wislocki sono uscite in registrazioni più o meno ufficiali) è stata commercializzata, nell’era del cd, solo dalla Brilliant Classic (nel BRILLIANT SET 9199) . In precedenza era uscita sull’isolato lp francese DISQUE CLUB DU NOUVEAU SIECLE DCNS 801, sul quale però nutro seri dubbi che il direttore fosse Eliasberg.

Ciò che però è assolutamente nuovo in questo cd è l’esecuzione delle Sonate beethoveniante nr.7 op.10 nr.3 in Re maggiore e nr.18 op.31 nr.3 in Mi bemolle maggiore da Mosca 1 aprile 1960, esecuzione che non era mai precedentemente uscita nemmeno tra le registrazioni amatoriali possedute dai collezionisti. Fra l’altro queste incisioni sono le prime che abbiamo dal punto di vista cronologico, in quanto di queste Sonate, che Richter eseguì moltissime volte e che tenne in repertorio per tutta la vita, avevamo finora esecuzioni dal 1965 in poi fino al 1992 ma nessuna così lontana nel tempo.

Quindi un disco molto molto interessante, da ascoltare con attenzione, plaudendo all’iniziativa della label russa, della quale consiglio di visionare il catalogo. (http://www.vistavera.com/index.php), ricco di molteplici proposte riferite a grandi artisti russi. Banale lo scarno libretto, ma indispensabile, come detto, il contenuto musicale del cd.

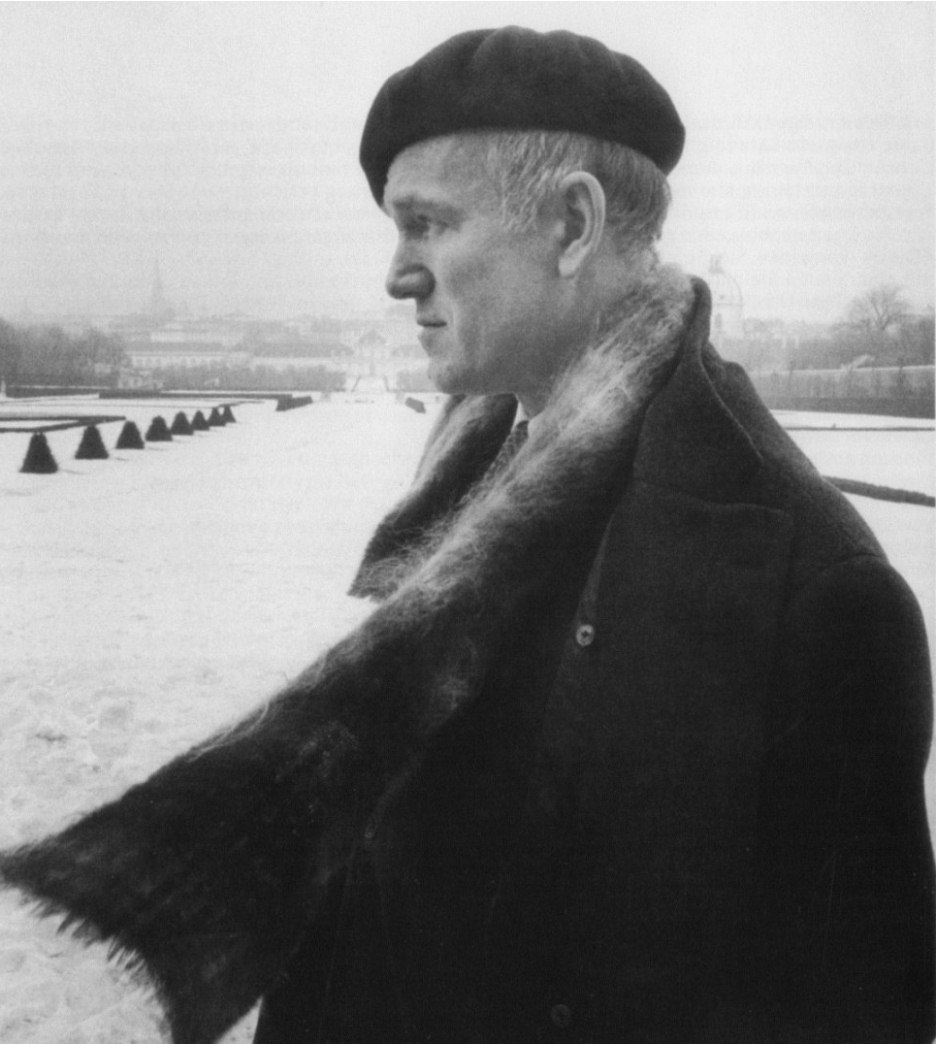

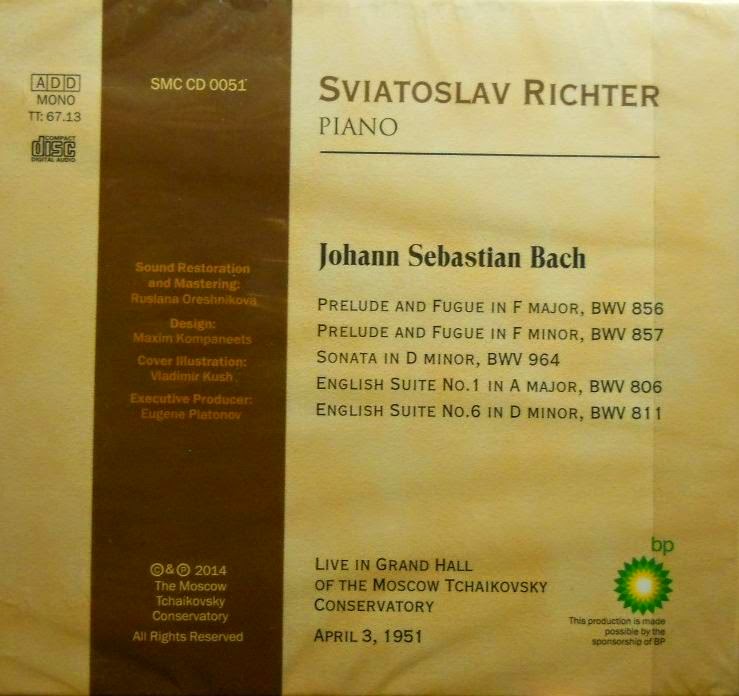

GREAT ARTISTS IN MOSCOW CONSERVATOIRE SMC 0051

Produzione straordinaria, ancora una volta, di questa etichetta che si auto qualifica come “Moscow Conservatory records” e che in quanto tale possiamo solo larvatamente immaginare di quali e quanti tesori musicali sia in possesso, non solo riferiti a Richter, se è vero, come circola voce, che tutti i concerti eseguiti al Conservatorio Čaikovskij siano stati registrati. Certamente non tutti in qualità somma, ma spesso la importanza di una registrazione “storica” con il suo grande spessore artistico predomina sulla ricerca della qualità audio perfetta e ce la fa apprezzare nonostante tutto.

Tale è il caso di questo straordinario concerto tenutosi nella Sala Grande del Conservatorio di Mosca il 3 aprile 1951. Sopravvissuto in registrazione amatoriale con alcune lacune in un paio di brani, viene ora riproposto ufficialmente nella sua interezza in una magnifica restaurazione operata dai tecnici russi.

Fa piacere che nel ben curato, anche se breve, libretto che accompagna un layout lussuoso - come sempre in questa etichetta – sia citato lo studioso e collezionista russo Yuri Bochonoff, propugnatore dell’iniziativa, che onora con la sua amicizia, sia il curatore di questo blog, sia alcuni suoi contributori, sia il sottoscritto.

Ma occupiamoci della musica.

L’ordine dei brani eseguiti nel concerto di cui sopra – un tutto Bach – fu il seguente:

1. SUITE INGLESE NR.1 in La maggiore BWV 806

2. SONATA NR.5 in re minore BWV 964

3. WTC LIBRO I: PRELUDIO E FUGA in Fa maggiore BWV 856

4. WTC LIBRO I: PRELUDIO E FUGA in fa minore BWV 857

5. SUITE INGLESE NR.6 in re minore BWV 811

Con i seguenti bis:

1. SUITE INGLESE NR.6 : SARABANDA

2. SUITE INGLESE NR.6 : GAVOTTA

3. SUITE INGLESE NR.6 : PRELUDIO

Altro elemento che aumenta l’interesse verso queste esecuzioni è che Richter eseguì le due Suite e la Sonata per la prima volta in pubblico in questa occasione.

Correttamente il libretto riporta l’ordine originale delle esecuzioni e spiega il motivo prettamente tecnico che ha portato ad una diversa progressione dei brani sul cd (sono assenti i bis).

Non sarà sfuggito all’appassionato richteriano i quaranta anni di distanza che separano queste esecuzioni delle Suite e della Sonata del 1951 dalla ripresa che Richter ne fece nel 1991, anno che vide decine di esecuzioni di questi brani in tutta Europa. Importante quindi per chi vorrà condurre una esegesi dell’arte interpretativa del Maestro questa distanza temporale tra brani medesimi, che segna non solo una evoluzione artistica ma di Pensiero.

SCHUBERT Richter Plays Schubert Live

Melodiya MELCD1002231

(4CDs)

Eccellente questa produzione della Melodiya, eccellente sotto tutti i punti di vista, tanto da consigliarne l’acquisto a tutti gli appassionati del nostro grande Maestro.

I dettagli si possono trovare nel seguito della nota. Qui vorrei evidenziare alcune delle perle contenute in questo cofanetto di 4 cd, facilmente reperibile online ad un prezzo assolutamente accessibile e conveniente. Novità esecutive, libretto, programmi manoscritti di Richter e tanta musica, tanto Schubert, tanta arte.

Che Richter sia stato il pianista che per primo, e non solo nell’Unione Sovietica, abbia recuperato l’arte schubertiana della Sonata mettendola allo stesso livello di un Beethoven è cosa nota, e se ne era ben accorto anche Glenn Gould, di cui non sto a ripetere il famoso aneddoto del suo ascolto di un concerto schubertiano di Richter del 1957 (vedi nota) 1]. E’ vero che in precedenza tale opera di recupero era stata fatta anche da Artur Schnabel, ma fu Richter il pianista moderno che diede nuova freschezza al sonatismo schubertiano liberandolo dalla polvere viennesizzante o dall’oblìo in cui era stato confinato.

In questi quattro cd troviamo esecuzioni finora mai commercializzate e quindi nuove per la discografia del Maestro (solo la Marcia D 606 da questa data era stata pubblicata precedentemente).

Troviamo due concerti completi (2.5.1978 e 18.10.1978) e una serie di piccoli pezzi raramente eseguiti da Richter, tra cui un paio in prima esecuzione assoluta.

Troviamo degli esempi di manoscritti richteriani utili, per chi non avesse mai visto la sua scrittura (anche se credo che la sua concertografia manoscritta sia ormai di dominio pubblico) a inquadrare la sua precisione e il suo ordine mentale.

Troviamo una qualità audio superba, un libretto interessante in russo, inglese e francese, un prezzo assolutamente onesto e accessibile.

Ma soprattutto troviamo Schubert, lo Schubert richteriano, il vero Schubert modernamente inteso.

Per chi fosse interessato all’acquisto online suggerisco:

oppure

CD 1

Sonata No. 6 in E minor, D. 566

Sonata No. 11 in F minor, D. 625

Sonata No. 13 in A major, D. 664

Recorded at the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on October 18, 1978

[INSIEME CON TRACCE 8-10 DEL CD4 COSTITUISCE CONCERTO COMPLETO DEL 18.10.1978]

CD 2

Sonata No. 18 in G major, D. 894

Sonata No. 6 in E minor, D. 566

Recorded at the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on May 2, 1978

[INSIEME CON TRACCE 1-7 DEL CD4 COSTITUISCE CONCERTO COMPLETO DEL 2.5.1978]

![]()

CD 3

Sonata No. 9 in B major, D. 575

Sonata No. 19 in C minor, D. 958

Recorded at the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on June 8, 1979 (D575), October 6, 1971 (D958)

CD 4

1 Scherzo No. 2 in D flat major, D. 593 – 6.05

2 Andante in A major, D. 604 – 4.46

3 4 Landlers from D. 366 in the order: D. 366/1 A major – D. 366/3 A minor – D. 366/5 A minor – D. 366/4 A minor – D. 366/5 – D. 366/4 – D. 366/1 – 5.36

4 Allegretto in C minor, D. 915 – 7.16

Moments musicaux, D. 780

5 No. 1 Moderato, C major – 5.38

6 No. 3 Allegro moderato, F minor – 2.04

7 No. 6 Allegretto, A flat major – 12.00

8 2 Ecossaises from D. 734 and 4 Ecossaises from

D. 421 in the order: D. 734/1 A minor – D. 734/2

A major – D. 734/1 – D. 734/2 – D. 421/1 A flat major –

D. 421/3 E flat major – D. 421/1 – D. 421/2 А flat major – D. 421/1 – D. 421/6 A flat major – 2.54

9 2 German Dances from D. 790 in the order: D. 790/8

A flat minor – D. 790/11 А flat major – D. 790/8 – 2.58

10 Impromptu in G flat major, D. 899/3 – 7.02

11 March in E major, D. 606 – 4.47

12 Impromptu in E flat major, D. 899/2 – 4.39

13 Impromptu in A flat major, D. 899/4 – 7.43

Recorded at the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on May 2, 1978 (1–7), October 18, 1978 (8–10), May 3, 1978 (11–13)

1]Videoconferenza tratta da "Richter The Enigma", di Bruno Monsaingeon, e in "No, non sono un eccentrico" Ed. EDTLa prima volta che lo sentii suonare fu nella Sala Grande del Conservatorio di Mosca nel maggio 1957. Iniziò il programma con l'ultima sonata di Schubert, quella in si bemolle maggiore. Si tratta di una sonata estremamente lunga, una delle più lunghe mai scritte, e Richter la suonò con il tempo più lento che io abbia mai sentito, rendendola di conseguenza ancora più lunga. A questo punto mi sembra il caso di fare una doppia confessione: innanzitutto, anche se a molti sembrerà un'eresia, sono ben lungi dall'essere un patito di Schubert e faccio fatica ad abituarmi alle strutture ripetitive tipiche di gran parte della sua musica; l'idea di dover restar fermo ad ascoltare i suoi interminabili tentativi mi irrita spaventosamente, è una tortura. Per di più detesto assistere ai concerti e preferisco ascoltare musica registrata nella solitudine di casa mia, dove nessun elemento visivo viene a inserirsi nel processo uditivo distraendolo. Ho confessato queste cose per dire che, quando sentii che Richter cominciava questa sonata con un tempo così incredibilmente rallentato, mi preparai a passare un'oretta alquanto agitata a contorcermi sulla poltrona. Ebbene, per tutta l'ora che effettivamente durò mi trovai in uno stato che non posso descrivere altrimenti se non come quello di una trance ipnotica. Tutti i pregiudizi sulle strutture ripetitive di Schubert erano scomparsi; tutti i dettagli musicali, che fino ad allora m'erano apparsi come appartenenti alla sfera dell'ornamentazione, assumevano improvvisamente l'aspetto di elementi organici. Avevo l'impressione di essere testimone dell'unione di due qualità apparentemente inconciliabili: un intenso calcolo analitico, che si rivelava però attraverso una spontaneità paragonabile all'improvvisazione, e in quell'istante - cosa che mi è stata ulteriormente confermata a più riprese ascoltando le incisioni di Richter - compresi di essere davanti a uno degli uomini con la più forte capacità di comunicazione che il mondo musicale abbia prodotto nel nostro tempo.